Music Streaming Platform

"Where words fail, music speaks", ― Hans Christian Andersen

Today, we will be creating an architecture for a service like Spotify or Apple Music. I recommend visiting these apps to have a better understanding of their functionality. These services are extremely popular; for instance, last year alone, Spotify and Apple Music generated revenues of approximately $4.1 and $5.5 billion, with their user base exceeding 600 million and 100 million monthly active users, respectively. Here you can find more detailed statistics.

There's a high chance you're using them too, or even listening to one of them right now while reading this article. So, I hope by the end of it, you will see what could be happening behind the scenes of your favorite music app!

The plan for the article is as close to a real-world scenario as possible. First, we gather the requirements from the business, both functional and non-functional. Secondly, based on our knowledge, we derive the technical estimations for our system, often referred to as "back of the envelope estimations". Thirdly, we outline the backbone of the system and API to support the functional requirements. Finally, we gradually scale our system out to meet all the non-functional requirements and consider potential pitfalls and trade-offs. Now let’s dive right in!

Functional Requirements (FR)

These are the requirements businesses will request. Stakeholders are generally not aware of all the intricacies of software architecture, so it is our responsibility to explain what is actually feasible and what is not.

Music streaming services, of course, come with a lot of functionality. We will limit our discussion to core features:

- Music streaming

- Music management (uploading, storage, removal)

- Music search

Let’s list the topics to keep out of scope:

- Authorization / authentication mechanisms

- Additional features:

- Marking a song as favorite / adding to library

- Social activity like following / followers

- Playlists (both user-created and automatically generated)

- Suggestion algorithm

- Legal compliance

- Subscriptions and payment management

- Marketing and customer engagement

- Advertisements on a free tier

- Analytics and reporting

- Logging and monitoring

These are all important features on their own, but we will not cover them in-depth to avoid bloating our design. However, we will briefly touch on some of them in the “Additional questions” section.

Non-Functional Requirements (NFR)

These are the requirements for how effectively our service meets its functional requirements. The list of possible non-functional requirements is too long so we need a strategic approach to their management. This section is divided into three parts: firstly, obtaining essential quantitative requirements (from the interviewer or stakeholders); secondly, making assumptions and estimations based on these numbers; and thirdly, discussing qualitative requirements.

Quantitative Requirements

Here are some external requirements we receive from the business or interviewer:

- Scalability. We aim for a globally used system, expecting up to 1 billion active users. By “active users,” we mean daily active users (DAU). This number is even greater than what YouTube typically sees.

- Latency. Latency is the time it takes for a user's request to be processed and the response to be returned. It is crucial for users to start listening to audio as soon as possible; hence, we aim to keep latency below 200 ms.

- Storage. We plan to store 100 million tracks

Estimations

Now it’s time to derive some estimations from the aforementioned NFRs.

This section already starts testing your ability to convert general business requirements and your understanding of various systems into technical considerations. To be successful in it, it is very important to have a a solid grasp of common parameters (such as the average size of files, network latencies, etc.) as these serve as the foundation for your estimations. I am going to gather a list of them in a separate post.

Here are some rough cheat sheet numbers:

- Audio blob (MP3, AAC): 5 MB

- Audio metadata (name, duration, author, etc.): 1 KB

- Average audio duration: 5 min

- User data: 1 KB

Another critical factor is understanding how daily active users interact with the platform, which can vary significantly across apps. For instance, Netflix might expect an average active user to spend about 2 hours watching content, whereas a Weather app anticipates only a handful of daily requests from its users. In our case, we estimate the average user's daily session to be 3 hours. As an upper bound, we can assume that at peak times almost all active users may be using our platform simultaneously.

Now, I will provide estimations for a single user. During the actual design process, we will scale out the system gradually and adjust these metrics at each step.

As we will see later audio files and other data (metadata, user data) should be stored separately so it makes sense to make estimations for them independently.

We calculate throughput for streaming data and requests per second (RPS) for other data since its transfers are relatively small.

Our expectation is that the majority of users will just press "play" on a predefined playlist. We assume that each user will make about 30 additional requests per session for searches and playlist updates.

Requests per second. For audio metadata and user data we get one request for the next track each 5 minutes which is 180 / 5 = 36 requests per hour. Plus we add 30 / 3 = 10 additional requests each hour. The result is (36 + 10) / 3600 ≈ 0.01 RPS

Read throughput. Each streaming request initiates a new long-lasting connection and requires high bandwidth to transfer the audio. Downloading a whole file at an average 3G speed of 5 Mbps would take 8 seconds, which greatly exceeds the acceptable latency of 200ms for song playback. That’s why we use streaming approach and load data continuously.

Streaming clients typically rely on the audio bitrate, which provides the necessary throughput to stream audio without lags. The bitrate is the number of bits used to represent one second of audio.

We estimate an average bitrate of 200 Kbps, though songs can be served at varying bitrates from 96 Kbps (low quality) to 320 Kbps (high quality). You can check Spotify's supported bitrates , and as mentioned, the actual bitrate may vary depending on network conditions, the user's device, and other factors, which we will discuss later.

If you were unfamiliar with bitrates, you could deduce the appropriate number yourself. For instance, aiming for the audio to arrive about twice as fast as the playback speed to pre-cache some audio data in case of network instability, you get 2 * 5 MB / 5 min ≈ 300 Kbps, aligning well with the mentioned bitrate ranges.

One might mistakenly base estimations on the maximum network bandwidth capacity, such as 10 or even 100 Mbps for a 4G network. However, this capacity is shared among all of a client's applications, and serving audio at maximum bandwidth would increase the load on our servers without significantly benefiting the client.

Read/write ratio. We assume that for 100 reads there will be 1 upload which gives us 1:100 ratio.

Writes per second: From the above we get 0.01 * 0.01 RPS = 10-4 RPS

Write throughput. Similarly we get 0.01 * 200 Kbps = 2 Kbs on average for streaming.

Storage. At first glance it looks like one track requires 5 MB of blob storage and 1 KB of metadata. However the reality is more complex.

Music labels upload music in lossless formats like FLAC or WAV to ensure the best possible source quality. These files may weigh as much as 50 MB. Given these files we need to compress them to more size-efficient formats like AAC, MP3, and OGG which give us previously mentioned 5MB. These formats balance sound quality against file size, making them suitable for streaming over the internet. Different formats are used for different devices: AAC for Apple devices, MP3 for broad compatibility, OGG for certain browsers. You can learn more about audio file formats.

On top of that to accommodate varying network speeds and device capabilities, audio files are transcoded into multiple bitrates. Common bitrate versions might include:

~96 kbps — low quality for slow mobile connections.

~160 kbps — medium quality for standard quality on mobile devices.

~320 kbps — high-quality on broadband connections.

Now as for estimations for each track we get 50 MB (original quality) + 5 MB * 3 formats (AAC, MP3, OGG) * 3 bitrates (low, medium, high) ≈ 100 MB total blob storage per track. Fortunately the metadata will stay the same and is still about 1KB per track.

We should also include the data for users. Each of them will have a list of basic attributes or references to other entities. We estimate the size per entity as 1KB and call it “profile” data. Real profile data size can be a lot more if we store user history and activity log but we leave it out of scope. Apart from that, we assume that we have 10 registered users per active user meaning 10 KB per active user.

It is still not the end. When considering scalability we should also need to double our storage to always have space for new writes. Hence the result is roughly 200 MB of blob data, 2 KB of audio metadata per track and 20 KB of profile data per active user.

On top of that the industry standard is to replicate data at least three times to keep the system durable in case of disasters. We won’t do these calculations but we imply them when mentioning data replication. You may also discuss forecasting the service usage growth for 10 or more years and adjust the required space accordingly.

Qualitative Requirements

We've bypassed several NFRs without estimations for multiple reasons. Some can be inferred from others, such as downtime being the inverse of availability. Others are not easily quantifiable. For example, measuring manageability or serviceability is difficult. These metrics assessing the ease and speed with which a system can be repaired or maintained. Even if you manage to quantify them, it might not significantly aid in the design process.

The same applies to performance, defined as the amount of work done by the system per second. This definition is somewhat broad, isn’t it? We can presume that performance is roughly synonymous with throughput and latency. The list could go on. Therefore, we will regard these and other requirements as qualitative metrics rather than quantitative.

Here are some qualitative requirements we will consider:

- Availability: This one is fundamental. Our service must be accessible to users in various locations. This metric is typically outlined in a Service Level Agreement (SLA) as the percentage of time the system is available to users, e.g., 99.999%. However, the exact figure doesn't translate straightforwardly to the design decisions. Thus, we will aim for an ideally unachievable 100% availability for simplicity.

- Consistency: Once a new track is uploaded, it should become available everywhere almost immediately. Achieving this is more complex than it appears. If you're familiar with the CAP theorem, you remember that it's impossible to achieve both consistency and availability in a distributed system. We will address this complexity later. Here, we outline the business requirements, and it is our responsibility to inform the business if they are feasible or not.

- Security: We won't delve into security in depth here but will discuss general considerations. Our primary requirement is ensuring that data is accessible only to the authorized users it's intended for.

- Fault Tolerance: The system's ability to continue operating properly in the event of failures in one or more components. It's crucial to identify potential single points of failure and provide redundancy for them.

- Usability: While it may seem trivial, we must periodically ensure our system isn’t over-engineered to the point of being problematic from user experience perspective.

- Reliability: It means the probability that a system will produce correct outputs up to a given time. This is another aspect we should revisit periodically. For instance, our design could allow a user clicking the play button twice to start two overlapping audios. Or, we could mistakenly serve ads to premium clients. As an engineer you probably know that there are plenty of places where things can go wrong.

Minimum Viable Product (MVP)

Now, let's outline our design. What I like to do is start with something as simple as possible that incorporates the functional requirements. After that, we will gradually improve this design to meet all the requirements.

As basic as it may seem, this schema is exactly how it appears to the user. Essentially, we have a black box hiding all the logic and the user interacting with it. This schema incorporates all the functional requirements and will help us not to lose focus later. Now, let's peel back the layers.

Data storage

After a request arrives at the service, it needs to retrieve data. We need to keep data in some kind of dedicated storage. If you want to be even more meticulous, you might consider proving why we can't store data inside the service's file system. For example, due to the need for the service to be easily redeployed and scalable.

Now, let's decide what kind of storage we need. To do this, we have to think about our business domain and the entities we are essentially working with. In this case, we are dealing with music or other audio data, typically stored as a blob in some audio format like WAV, MP3, etc.

However, this is not sufficient as our users will also need the track's name, author, maybe a description, subtitles, and so on. To efficiently manage this data in our service, we will most likely need to store this information under a unique track ID.

Considering all these properties, we can see that the audio data itself is quite different from the data describing it, also known as metadata. Placing blobs in a traditional database would drastically decrease its performance and increase costs. Here is a good article explaining why. Thus, it would be more efficient to store the blob data in an object storage, which is highly optimized for it, while more structured and less voluminous metadata and profile data will be stored in a database.

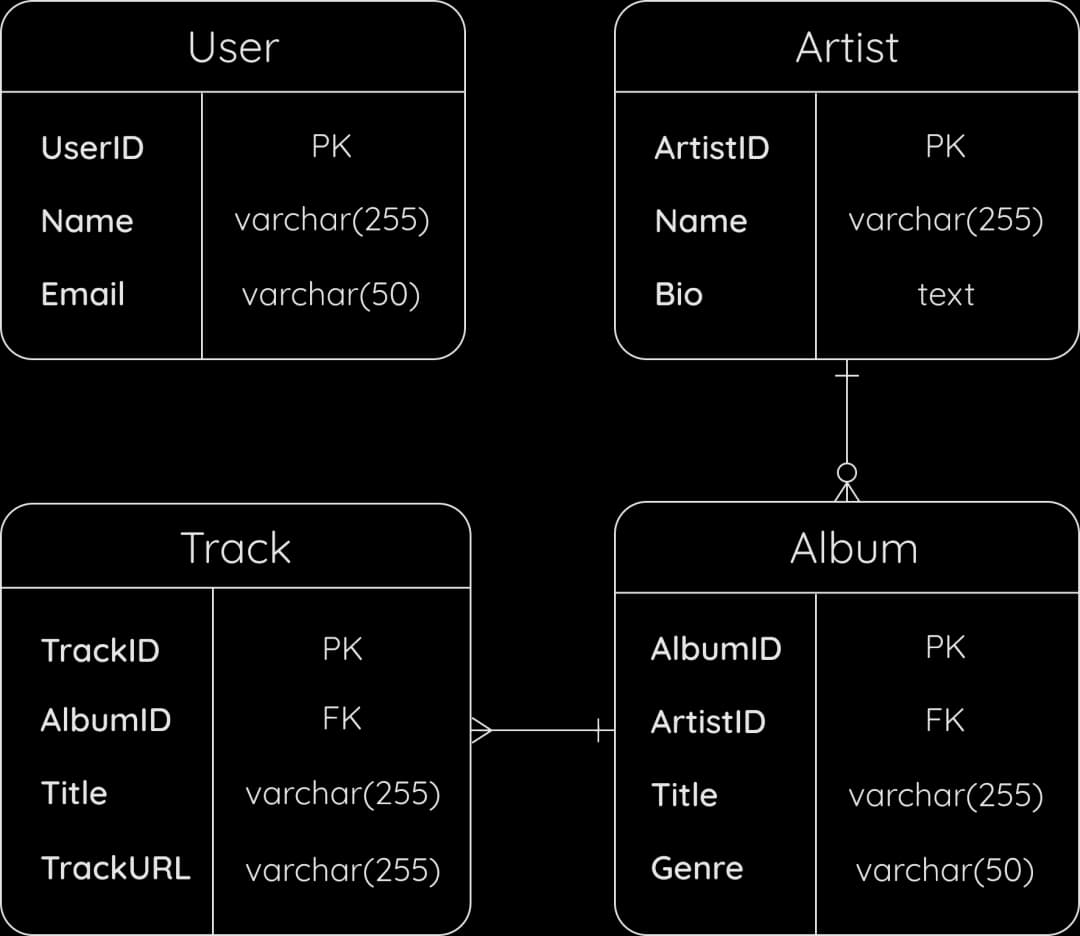

Now let's discuss some of the entities we will focus on:

- User: The actual user of the app, most likely having attributes such as name and email. I do not mention fields like subscription type or password hash, as we have intentionally left them out of scope.

- Track: Consists of a blob and metadata, as we have discussed. It may include fields such as title, duration, and a link to the actual location of the blob in object storage.

- Artist: A band or individual who uploads tracks. May include fields like name, biography, country, etc.

- Album: A collection of tracks by an artist, with properties such as title, genre, release date, etc.

- Playlist: A compilation of tracks generated by a user, platform administrators, or a suggestions algorithm. May have fields like title, and whether it is public or private, among others.

I omitted supplementary columns like "created_at", "updated_at", and "deleted_at", although they are implied by default for efficient retrieval and indexing.

Of course, there may be more entities in a real app. It's your choice where to stop. I decided to list these ones to better illustrate our domain and to reason about the data storage type later.

With this in mind, let's choose the storage type for metadata. Generally, we have two high-level options to consider: either relational or non-relational database solutions. Here are the reasons why I opt for the SQL solution:

- Entities Hierarchy: The structure of each entity is relatively flat and does not have deeply nested fields. The relationships are quite clear.

- Structure Changes: The structure is well-defined and is not expected to change significantly. We don't have data flow from external systems which could change the data structure uncontrollably.

- Data Writes: The read-to-write ratio indicates that writes are much less frequent. Each write usually involves a single entity, like audio being published / modified or a user registered / edited. These events do not occur as frequently as, for example, logs or analytics events.

- Queries: Our queries will rely on referential integrity and include joins to retrieve data. We will also benefit from database schema restrictions and ACID compliance (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability), preventing records with the wrong structure or empty fields from entering the database and keeping the database in a consistent state.

- Data Locality: Despite our entities being relatively straightforward, even if we end up extending them significantly with additional fields for some reason, we don’t expect to retrieve all these fields for most requests. Generally, we only need a small portion relevant to the current view or service.

This is our architecture so far:

However, every choice comes with its trade-offs. By opting for a relational database, we also inherit all its challenges, such as difficult horizontal scaling and additional overhead for query processing to maintain ACID compliance.

Here is the sketch of our Entity Relationship Diagram (ERD) and this is a good introduction on how to interpret and draw your own ERDs. The User entity appears standalone as we've opted out of subscription or marking as favorite functionality. We also assume that one user can play only one track at each moment in time.

It is reasonable to treat artists separately from users as they will have a very different scope of use cases and permissions. This separation aids in decoupling these entities in the codebase according to the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP), as each entity will have its own reasons to change. Each artist can have zero or more albums, and each album contains at least one track. In our design, a standalone track is treated as album with one track.

Data management

Now, let's discuss data management, best explained through the backend API. We'll define the necessary endpoints to handle user actions such as uploading and streaming music, in accordance with the functional requirements. When in doubt, you can refer to the freeCodeCamp article on API design best practices. Considering the importance of backward compatibility and potential API updates, I have also incorporated a versioning prefix.

Entities like user, album, and artist are straightforward to create, read, update, and delete (CRUD), making the API for them simple. Therefore, I will skip them and instead focus on tracks management. Most operations with tracks require several steps.

The first step is obtaining a pre-signed URL. Pre-signed URLs provide time-limited access to a file directly in a designated bucket in object storage. Here's an example of a pre-signed URL for AWS:

https://s3.amazonaws.com/music-bucket?X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIA3SGQVQG7FGA6KKA6%2F20221104%2Fus-east-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20241115T140227Z&X-Amz-Expires=3600&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Signature=b228dbec8c1008c80c162e1210e4503dceead1e4d4751b4d9787314fd6da4d55The second step involves retrieving or manipulating the data in object storage using the given URL. After successful completion, the final step is to send new metadata to the server, if applicable.

Getting a track:

-

The server receives a request to stream a track:

GET /api/v1/tracks/:trackId/stream -

The server checks if

trackIdexists (sends404 Not foundif not) and retrieves the track's metadata from the database, including the path to the audio file in object storage -

The server checks if the requesting user has permission to access the track (we will talk about it later)

-

The server responds with

200 OKand body with a pre-signed URL to the audio file in object storage:{ "trackUrl": string, "albumId": number, "title": string }Alternatively it could also initiate stream of the audio data to the client but using a direct URL is more efficient since it offloads the data transfer work to the object storage service, which is optimized for such operations

-

User starts streaming the track from object storage with the given URL

Uploading a new track:

-

The client first obtains a pre-signed URL from the service

GET /api/v1/tracks/upload-url -

The client uploads the audio file directly to the object storage using the pre-signed URL. Upon successful upload, the client receives the URL or path to the stored file

-

After the successful file upload, the client issues a request to the

/api/v1/tracksendpoint, including the metadata and the URL of the uploaded audio file as part of the request bodyPOST /api/v1/tracks { "albumId": number, "title": string, "trackUrl": string } -

The server receives the request and validates the provided information

It checks if the

albumIdexists, validates thetitleand other fields, and confirms the file URL is valid and accessible -

The server then creates a new record for the track in the database, storing the metadata along with the reference to the audio file's location in object storage.

-

The server responds with

201 Createdoften including track’s metadata

Updating a track:

This API breaks down into two separate requests: updating metadata and updating blob file.

-

In case of blob update client issues

GET /api/v1/tracks/update-url/:trackIdrequest and directly uploads the file with the pre-signed URL in the response -

The client sends request to

PATCH /api/v1/tracks/:trackIdRequest body for metadata:

{ "albumId": number, "title": string }Request body for blob file:

{ "trackUrl": string } -

The server validates the request and updates the track's metadata in the database and cleans up previous file location in the object storage.

-

The server returns

200 OKoften including the updated metadata for confirmation

Deleting a track:

Pre-signed URLs are not used for delete operations from the client side due to security concerns. Delete operations are usually managed by the server, which authenticates the request before deleting the resource.

- The client sends

DELETE /api/v1/tracks/:trackId - The server validates the request and user permissions

- The server deletes the file and metadata and responds with

200 OKoften including ID of deleted track

Streaming

Streaming is the core component of our system. Sending the entire file over the network as a response is not an effective approach. It may take several seconds for a full file to download before playing, which is significantly more than the 200ms latency we aim for. So, how can we maintain low latency and ensure smooth audio playback, especially if the user has a low-performance device or poor network connectivity?

Fortunately enough, modern streaming platforms utilize high-performance protocols for this purpose. These protocols incorporate Adaptive Bitrate Streaming (ABR), which allows the streaming service to provide an uninterrupted listening experience despite network fluctuations and even when the network bandwidth is consistently low.

Currently, there are two widely adopted protocols: HTTP Live Streaming (HLS) developed by Apple and the open-source MPEG-DASH (Dynamic Adaptive Streaming over HTTP). The latter is not supported by Apple devices.

These protocols function by dividing the audio stream into a sequence of small, HTTP-based file downloads, each containing a short segment of the audio stream, typically lasting 2-10 seconds. For instance, MPEG-DASH also supplies an XML manifest file listing various bitrates that the client can request.

The client's media player reads the manifest file and decides which quality level to download based on the current network conditions, CPU usage, and buffer status. The client fetches the segments sequentially via HTTPS GET requests and plays them back without interruption. If a quality adjustment is necessary, it switches to a higher or lower quality stream by selecting segments from the respective stream as indicated in the manifest.

HTTP/2 helps reduce the overhead of new network connections by multiplexing requests and responses over a single long-lived connection.

At this stage, we have a system that will likely function well for a few users and meet the functional requirements. We are now entering the most intriguing and challenging phase, encompassing all the trade-offs, controversial topics, and debatable solutions that will vary depending on the non-functional requirements we aim to fulfill.

Think of this part as working with a LEGO set. You're starting with a simple car. It's time to snap on those special LEGO pieces that will give it all the extra powers it needs to tackle different challenges.

Scaling Out

Although scalability is just one of the non-functional requirements, I place it here as the consolidating one. Our goal will be to scale our service gradually from 1,000 to 1 billion active users while meeting all the other necessary non-functional requirements like availability, low latency, and security. We will strive to find a balance between cost and manageability on one side, and performance and reliability on the other. To help you see how we address NFRs, I highlight them with italic font.

1K active users, 100K tracks

Here are the estimations made from multiplying the previous numbers for a single user or track:

- Read RPS: 10

- Write RPS: 0.1

- Read throughput: 200 Mbps

- Blob data: 20 TB

- Audio metadata: 200 MB

- Profile data: 20 MB

Computing layer

With these numbers, our current prototype will work just fine. A well-optimized single server instance can handle 100 RPS with ease. However, this server is a single point of failure. We need to keep our system available in case a server breaks for some reason. For that, we will keep two instances of the service on two machines. In case of server fault, we can have an auto-restart mechanism and some monitoring and alerting system integrated so that engineers are notified about the problems.

One thing I intentionally skipped in the MVP section is music preprocessing. As we mentioned in the estimations part, audio files should be compressed to reduce their size for streaming. Different devices may support different audio formats, hence the need to store several lossy compression formats: AAC for iOS devices, MP3 for broad compatibility, OGG for certain browsers. This process is called encoding. On top of that, we need to serve each format in multiple bitrates suitable for HLS or MPEG-DASH. This process is called transcoding.

So, we add two service workers called transcoder and encoder forming a processing pipeline to our design. The encoder service will also post new file metadata and its location in the object storage to the SQL database. With these we address both increase availability and decrease latency.

In theory, we could have a live transcoder setup, but it would significantly increase the latency of our service and require substantial computing resources. Instead, we will opt to pay more for storage and process the music preemptively in the background, benefiting from faster start times for playback and minimized buffering.

Data layer

We successfully reduced the load on our computing components, but what about storage? Both of our servers will end up constantly connecting to a single database instance. Establishing a new connection for each request is costly, so to reduce latency, a better approach is to use connection pooling.

Since the database and object storage are stateful, keeping a second instance for redundancy at this point seems to be relatively costly. At this scale, it is arguably easier to make backups every couple of hours compared to configuring read replicas, as it comes with new challenges that we will discuss later. The actual backup strategy will depend on the Recovery Point Objective (RPO) and Recovery Time Objective (RTO) that the business can tolerate.

Although 100 connections for streaming with potential bursts may seem high for a single database, they will go to our object storage instead, which is well-optimized for it.

To decrease latency, we should also think about properly indexing our database. Most probably, we will index tracks and albums based on their "name" and "created_at" fields for efficient searching. Other indexes may also be applied based on specific use cases of your app. However, remember that using indexes too much can negatively impact write performance and significantly affect query performance.

Network layer

To distribute the traffic between two server instances, we need a load balancer. Whenever we introduce a load balancer (LB), it is good practice to discuss the algorithms for distributing traffic and the level at which they operate. By level, we mean the layers in the OSI model. LBs can generally operate at two levels: L4 — network and transport level, routing based on TCP/IP; and L7 — application level, routing based on HTTP. If you are not familiar with LB concepts, you may find this quick intro helpful.

In our case, a simple L4 round-robin LB will suit our needs. Round-robin is simple to work with, and L4 is faster and more appropriate as we don’t have to distribute traffic based on information in the HTTP requests. We don't need sticky sessions either as the streaming will be held by the object storage. The LBs can also be either hardware or software, with hardware-based being more robust and performant but more expensive. In our case, a software LB (like HAProxy) is better, as the load is relatively small and it is more configurable.

We should also outline a network boundary to emphasize the private network, accessible from the outside only through the load balancer or another reverse proxy. Speaking of which, although the client connects to the reverse proxy using HTTPS, it is good practice to enable TLS termination to increase the speed of communication inside the cluster by avoiding encryption-decryption overhead.

Another point to mention is that our transcoder and encoder need to communicate with one another to form a pipeline for audio processing. They perform their jobs at different speeds and need to communicate asynchronously. The best way to achieve this is by using a Message Queue (MQ).

Lastly, for the sake of completeness, I will also add the Domain Name System (DNS), as it is the first component in the user request flow to interact with and essential for converting a domain to an actual IP address of our reverse proxy.

Security

Before we delve further, let's briefly discuss security. Although security is not our primary focus, it is crucial to address it. We have already decided that the authentication and authorization logic will be abstracted as a service. It is good practice to include this in our design. We will represent it as a "black box" in our schema. It could be anything from an enterprise SAML SSO solution to a third-party provider built on OpenID and OAuth 2.0 protocols. Regardless of the actual implementation, we assume that after providing valid credentials, the user receives either a stateless token, like a JSON Web Token (JWT), or a stateful session ID.

This AuthN/AuthZ service will be operational within our cluster. The backend service will contact it for each request (perhaps through middleware) to validate the token and introspect it to obtain the user ID. The token will also enable us to provide Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) for the music, since every authenticated user can stream the music, but only artists can upload and delete tracks.

Security itself is a vast topic, so I leave other intriguing aspects like OWASP Top 10, DoS protection, intrusion detection systems, poisoned pipeline execution, and many more for your own exploration.

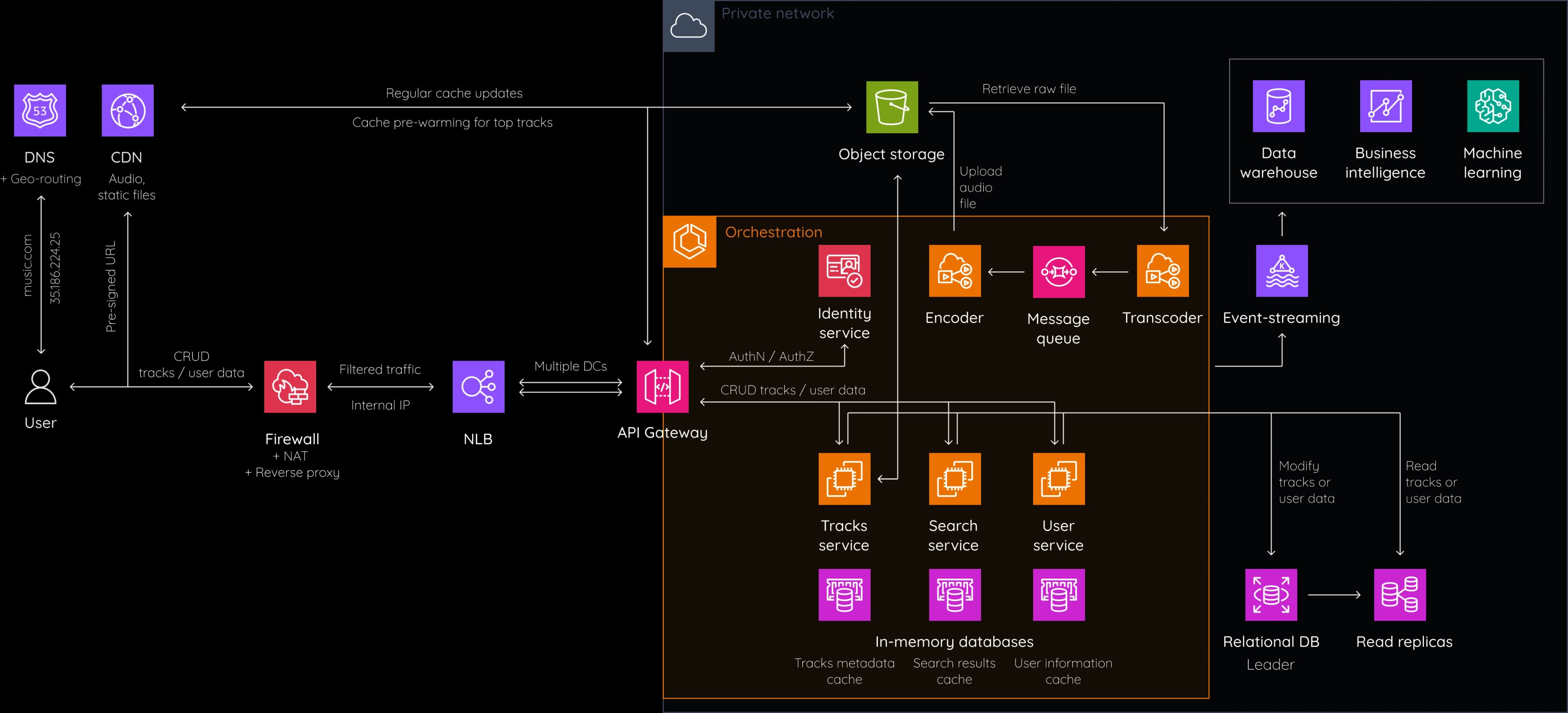

Let’s see what we have so far:

The cloud symbol doesn’t necessarily imply a cloud-native system; rather, it helps to delineate the boundary between public and private network.

10K-100K active users, 1M tracks

Upper bound estimations:

- Read RPS: 1K

- Write RPS: 10

- Read throughput: 20 Gbps

- Blob data: 200 TB

- Audio metadata: 2 GB

- Profile data: 2 GB

Let's see how this will influence our system.

Data Layer

Starting with the data layer, although 2 GB of data is not excessive for a database, the number of read RPS is quite high for a single database to handle, especially during peak hours.

There are several strategies to mitigate this. First, we can separate profile and metadata into two databases, as they exhibit different access patterns. Music information is accessed far more frequently than user data. Additionally, reads occur 100 times more often than writes. Therefore, we can optimize the metadata database workload by introducing read replicas.

But how do we maintain data consistency between them? According to the CAP theorem, we have to sacrifice either consistency or availability to maintain system partition tolerance. Moreover, even when the system has a coherent network, the extension of the theorem, known as PACELC, dictates that we need to choose between consistency and latency.

In the context of a music streaming app, it seems reasonable to sacrifice consistency in both scenarios. In other words, we opt for eventual consistency for read replicas. This means that new writes may take some time to propagate to all replicas asynchronously. We can inform the user that updating profiles may take some time to reflect. Uploading music requires even more time as it needs to be processed by the service workers. This approach benefits availability. For fault tolerance, we can also add a standby replica where data is replicated synchronously. We can switch to it in case the primary write replica goes down.

Replication is also applicable to object storage but is usually managed behind the scenes. You can easily scale it horizontally by adding new machines if you need more storage.

Computing layer

Now let's discuss the computing side. The load is high, and if one of our servers shuts down, the other can easily become overwhelmed, especially during peak hours. To overcome this, we can add more servers. However, managing a large number of servers manually can be cumbersome and costly, as you need to monitor and update each one separately. Moreover, we will have different teams working on various parts of the platform that need to keep in sync with each other while being independent in their workflows and releases.

To address these issues, it is better to split one monolithic service into microservices. For example, the first one could be responsible for searching music, the second for streaming, the third for uploading and managing music, the fourth for user data management, and so on. This lays the foundation for future scaling.

In order to streamline new releases and maintain a reproducible environment between services, we deploy them as containers. To monitor them, we will use an orchestration tool (like Kubernetes or AWS ECS in the cloud) where essentially a number of machines (aka nodes) is abstracted as a cluster. For each new deployment, the orchestrator spawns the predefined amount of containers (pods) for this microservice and keeps checking their health status. It also gracefully shuts down the previous versions of the container.

This modular approach decouples applications from the underlying infrastructure, providing greater flexibility and durability while enabling developers to build and update these applications faster and with less risk.

Microservices also offer another benefit: each one can be optimized for its specific job. For example, an audio uploading service will work only with the write replica and can benefit from more CPU resources. Conversely, a searching service will access only read replicas and can integrate tools like Elasticsearch and utilize more RAM.

One could go even further and split the microservices into layers, such as a presentation layer where each microservice adapts information for each client’s platform type, or a data access layer where services are dedicated solely to retrieving data from the database or cache efficiently, among others. Our current scope doesn’t require this level of granularity.

However, microservices are not a silver bullet. All the tasks you would perform once for a monolith need to be repeated for each service and kept up to date. This includes versioning, testing, monitoring, documenting, etc. Given that they are usually managed by different teams, this brings new challenges for the company to streamline and unify the processes. You can read about alternative architectures here.

Network

To efficiently distribute traffic across microservices, we need an effective routing solution. For this, we will use an API Gateway. It acts as a front door to the cluster and is also responsible for token introspection and validation in tandem with the authentication service we mentioned earlier.

Additionally, we must ensure that a disaster in the zone where all this infrastructure is located will not bring the platform down, so we need at least one more data center situated far away from the other. To distribute the traffic between the data centers (DCs), we will continue to use a Network Load Balancer (NLB) with perhaps least connection algorithm.

To make our system more resilient, we will add a special reverse proxy that will implement Network Address Translation (NAT) for outbound traffic, act as a firewall as a security precaution, and apply rate limiting on API endpoints to control the number of requests a user or IP address can make within a specific timeframe.

Rate limits can depend on the types of operations. For example, actions like track uploads or playlist creations could have stricter limits compared to track playback or metadata retrieval. They can also be adjusted dynamically based on system load or user behavior. We can also encourage or enforce rate limiting on the client side using throttling and debouncing techniques.

Another point to discuss is interservice communication. While edge microservices work with HTTP traffic incoming from the API gateway, they can utilize more efficient protocols like gRPC for synchronous calls to other internal services.

We also need to consider asynchronous communication. Most likely, we will want to keep track of user activity. For instance, each time a user plays a song or adds it to a playlist, we may want to emit an event or message that will later be processed for analytics or machine learning (ML) services. While messaging queues help us in communication between two microservices to decouple services and handle a large amount of events centrally, it is better to use an event streaming platform (like Kafka) that can support many independent subscribers listening to the topics they are interested in and capable of processing millions of events per second.

Caching

There is one more problem that layers of microservices and additional network communications introduce, which is latency. All this infrastructure significantly increases the time for interservice communication, while our initial goal was to fit the response time within a 200ms latency budget. To address this issue, we will utilize caching at different layers, from the closest to the user to the closest to the data itself.

First of all, we can cache rarely changed and small-sized information like user data, playlists, thumbnails, and audio metadata information right on the user’s device.

The next layer would be the Content Delivery Network (CDN) to cache audio files, metadata, images, and other public static content at edge locations closer to the users. This dramatically reduces latency and bandwidth costs by serving content from geographically distributed servers. Popular tracks or metadata can be pre-cached based on usage patterns and heatmaps, ensuring that frequently accessed data is readily available. Geo-routing (probably DNS-based) helps direct users to the nearest server or CDN edge location.

The CDN can be configured to dynamically load new content from object storage. We can also preemptively load new releases from popular bands when high load is expected or pre-cache the top 500-1000 tracks based on our analytics data. In case of a cache miss we will use a common cache-aside (lazy loading) pattern to add data to the CDN after it was returned to the user from the database.

The next deeper cache layer will be within our application, which is in-memory caching solutions (like Redis or Memcached). It can store least recently used (LRU) data such as user data and audio metadata. We can also cache the results of common queries and computations. Using in-memory caches for audio blobs is generally not recommended due to their large size and hence expensiveness. We can configure each microservice to use its own in-memory cache.

Furthermore, we can utilize the built-in caching mechanisms of our database to cache frequently accessed data. By the way, read replicas already effectively act as a sort of cache layer for the primary database.

However, caching can easily go wrong. To prevent cache overflow, we need to establish correct cache eviction policies and regularly monitor the heatmaps.

Now our system is ready to serve up to 100,000 users. We have an API Gateway as a secure entry point to each cluster and numerous microservices fine-tuned for their specific job, as well as a database and object storage with read replicas and cache layers.

1M-100M active users, 100M tracks

Upper bound estimations:

- Read RPS: 1M

- Write RPS: 1K

- Read throughput: 20 Tbps

- Blob data: 20 PB

- Audio metadata: 200 GB

- Profile data: 2 TB

These numbers suggest that users may frequently access our system from different locations around the world. However, the majority of them are most likely still located in one or two geographical regions. This largely depends on the business case. Let's review our architecture again, layer by layer.

Data Layer

The key change here is that the write load can no longer be handled by one database alone. This means that we have to create multiple write replicas. This brings the consistency problems to a whole new level. Before, we had only one write database as a single source of truth, and our goal was to make read replicas follow it reliably. With multiple write replicas, there is no longer a single source of truth, and we encounter problems involving conflict resolution and achieving consensus.

There are mainly two solutions to allow writes in different data centers: multi-leader and leaderless replication. Both approaches increase the system's availability and fault tolerance but provide very weak consistency guarantees, which is not a problem in our case as we can tolerate eventual consistency. We will not go in-depth on these topics here.

Fortunately, there already exist solutions that allow us to deal with multiple write nodes. Although multi-leader replication is inherently supported in SQL databases, PostgreSQL BDR (Bi-Directional Replication) and Tungsten Replicator for MySQL have poorly implemented conflict detection techniques in many of them. The leaderless approach allows writes and reads from any node and has gained more popularity with its open-source implementations like Voldemort and especially Cassandra.

Cassandra has built-in capabilities to manage data replication across multiple data centers, configured to use an appropriate replication strategy (NetworkTopologyStrategy) and consistency levels (LOCAL_QUORUM, EACH_QUORUM, etc.) to meet the application's consistency and latency requirements.

Cassandra automatically shards data across the cluster using the concept of "partition keys". Internally, it relies on consistent hashing using a token ring. An optimal partition key ensures that the data is evenly distributed across all shards, thereby preventing any single shard from becoming a bottleneck due to uneven load. We will use Cassandra for both metadata and user data.

Using the User ID as the partition key for user data facilitates an even distribution of user data and aligns well with the fact that most operations with data are user-centric. We will also need to reengineer the data from relational to denormalized to make it compatible with Cassandra.

Partitioning metadata by Artist ID or Track ID alone is not a good option, as it might lead to uneven distribution since some artists and tracks are more popular than others. Some nodes could become hotspots, especially if a new release by a popular artist just dropped. To overcome this, it is useful to add a composite key consisting of a partition key and a sharding key (random number % number of nodes).

For object storage that contains our media files, support for cross-region replication is usually available out of the box. Similarly it implies high availability with a sacrifice in consistency.

Computing Layer

Computing servers will benefit from vertical scaling by adding more power and horizontal scaling by deploying more containers in different zones and regions, while the microservices architecture will inherently remain the same.

At this point, we should replace any stateful components, if we still have any, with stateless ones. This implies using self-contained tokens instead of sessions. It will also help us eliminate session affinity in case of application load balancers (ALB) and simplify load distribution. On top of that, it will ease the fault tolerance and recovery process, as we don’t have to worry about reconstructing lost session states.

Network

Although our current task specification covers only a couple of services, in real life, there will be many more addressing different aspects of business logic.

Just imagine how challenging it can be to establish and monitor all the interservice communication and traffic. It would be advantageous to abstract and unify this logic in the form of a sidecar for each service pod and manage it centrally. This is exactly the problem that a service mesh (like Istio or Linkerd) solves.

If you are not familiar with the concept of a service mesh, here is a good video introduction. A service mesh injects a proxy sidecar for each pod and uses a control plane to gather information about inbound and outbound traffic. It helps to increase serviceability and manageability with features like tracing, monitoring, service discovery, load balancing between service instances, efficient troubleshooting, and optimization.

It also enhances availability and resilience with setups for retries, failovers, circuit breakers, and fault injection. As a bonus, it also facilitates canary deployments and A/B testing by splitting traffic. Of course, adding a service mesh comes with the trade-off of additional complexity and potential vendor lock-in.

With the number of users close to 100 million, located in different geographic regions, it is time to think about Global Server Load Balancing (GSLB). It's used for global traffic management between data centers in different countries and even continents, directing users to the closest or most responsive geographic endpoint. GSLB often uses DNS load balancing as a mechanism to direct traffic but combines DNS with additional capabilities like health checks, geographic routing, and application performance considerations.

Traffic will land on our reverse proxy with firewall and DoS protections and then will be distributed within the region with NLB. Modern NLBs are capable of handling millions of requests per second.

Cassandra is already well-equipped to handle cross-data center replication efficiently and can VPN to communicate between nodes.

1B active users, 100M tracks

Estimations:

- Read RPS: 10M

- Write RPS: 10K

- Read throughput: 200 Tbps

- Blob data: 20 PB

- Audio metadata: 200 GB

- Profile data: 20 TB

Congratulations, we've finally reached the goal we set at the start. Interestingly, 1 billion active users would imply 10 billion registered users according to our estimations. At this point, every person in the world is registered, and some are registered twice 🙂. So, this scenario is mostly hypothetical speculation.

For the most part, our previous architecture will fundamentally remain the same but with significantly more vertical and horizontal scaling and data centers all over the world. To cut costs and increase security, it can be arguably better to maintain our own servers and fine-tune them to increase availability and decrease latency, as cloud providers may not be capable of meeting all of our specific requirements.

We will also need to establish ultra-low-latency communication between the data centers via a dedicated wired network. On top of that, optimizing network routing and agreements with Internet service providers for enhanced connectivity would be beneficial too.

Most likely, we will be hiring PhDs to invent and develop new approaches to push the limits of existing architecture solutions.

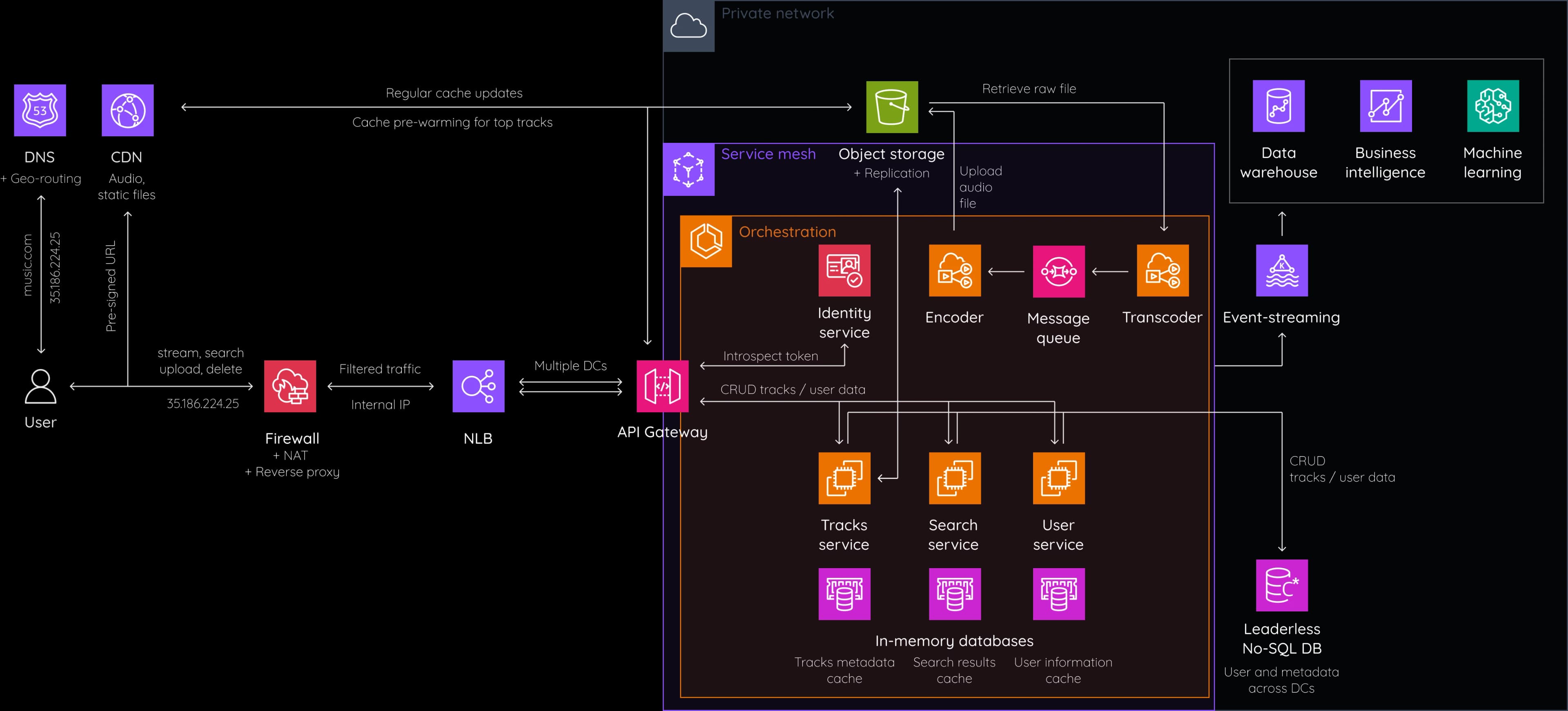

This is our final architecture:

Let's sum up the flow of the user's requests. First, the client contacts DNS to get the domain name. At this scale, we use DNS-based geo-routing to forward the request to the nearest region. The reverse proxy, acting as a firewall and NAT gateway, filters the traffic and translates the public IP address to the internal IP address. The round-robin load balancer distributes the traffic between data centers. The API Gateway receives the request and validates the token with the help of the identity service in the cluster. Then, the API Gateway sends the request to the corresponding microservice based on the HTTP route. Each microservice checks if data is available in the cache and polls the No-SQL database otherwise.

Upload requests end up creating a new audio blob in the object storage using an issued pre-signed URL and creating a new audio metadata entry in the DB. It also triggers the transcoding / encoding pipeline to prepare optimized audio files. Update and delete requests behave similarly. Stream requests result in streaming from the CDN using a pre-signed URL or from S3 directly if the entry is not found on the CDN. CDN and other caching layers use LFU or LRU strategies to continuously remove rarely accessed data.

Object storage data is replicated across regions. Database updates are continuously synchronized between data centers based on a leaderless architecture. The service mesh helps to monitor the traffic between microservices. The event-streaming service receives various events across the cluster and allows other subscribers to act upon them.

Additional Questions

Here are some more exciting challenges that you might think about or investigate on your own:

-

What if a new release by a popular band drops? How should we deal with a steep spike in traffic?

We have covered this topic in general, but you can reiterate through the system components and double-check if they are all actually capable of handling high traffic and how they will behave.

-

How do we keep the system fault-tolerant? What if one server fails or a whole data center faces a natural disaster?

Again, you can double-check the system for possible single points of failure and failover behavior. You may estimate the Recovery Point Objective (RPO) and Recovery Time Objective (RTO) for the system to guide disaster recovery planning and data backup strategies.

-

How would you describe the architecture of the frontend part?

I would assume a microfrontend architecture for the frontend app, as it plays well with the definitive purpose of each component like player, search, playlists, etc. Each component can be developed by its own team, have its independent failover behavior, version strategy, and releases.

Additionally, mobile apps should have the capability of downloading music for premium users and keep seamless UX when the user is offline. Special attention should be paid to accessibility in accordance with best practices and guidelines such as WCAG.

-

How to deal with legal compliance?

There are quite a lot of legal constraints you should keep in mind. Apart from regulations like GDPR in Europe, there are things specific to music streaming. A record label may decide to give the license for streaming in one country but not in another.

To address this problem we can map the user’s IP address to a physical location based on a geolocation database. We also need to maintain a comprehensive database of licensing agreements that details which tracks or albums can be streamed in which countries. We can then dynamically decide if a user has access to a specific track based on his or her location.

The music stream is often encrypted, with keys managed by the Digital Rights Management (DRM) system to prevent unauthorized access.

We should also perform copyright infringement checks for newly uploaded tracks. A technique known as audio fingerprinting is used to identify music tracks by analyzing the audio signal and generating a unique fingerprint or signature. Additionally, we can have a dedicated service worker continuously checking the content library for potential infringements.

-

How to insert ads on a free tier?

I propose that we keep a counter of tracks a user has listened to, and each time the counter hits a predefined value, reset it and load an ad before the next track.

-

Should we use cloud-native or on-premises solutions?

The system we described is not bound to either cloud or on-premises dedicated infrastructure. You may want to evaluate the costs and benefits of each approach.

-

How to handle analytics and gather users' activity data properly?

Although I included Data Warehouse or Business Intelligence components in the final diagram, in fact, they encompass a huge effort of careful system design and implementation. You need to gather an immense amount of user activity data, establish robust data pipelines, and carefully deliver it in a well-prepared form to analysts, business stakeholders, data scientists, and machine learning specialists so that they can reliably perform their jobs.

-

How to manage playlists and implement Spotify’s famous music recommendations algorithm?

Spotify's catalog comprises over 4 billion playlists. They can be user- or machine-generated. Users may add and delete tracks, share playlists with each other, fork public playlists and modify them.

The recommendation algorithm itself is Spotify’s secret recipe. They even have a feature to generate playlists based on one track. All these challenges can be an exciting system design task for data science and machine learning specialists.

Conclusion

We've covered a lot more than what can realistically be described in a 45-minute to 1-hour interview (unless you're Eminem, at least). The aim was to provide you with the opportunity to dive deeper into certain areas, depending on what the interviewer asks or what stakeholders deem important.

Remember to always keep in sync with the interviewer (or stakeholders) and decide your next path based on their comments. I hope this article was helpful to you, and I am always glad to receive your feedback. Stay tuned for more, and have a good day!